The Citizen-Soldier: Moral Risk and the Modern Military

The rumor was he’d killed an Iraqi soldier with his bare hands. Or maybe bashed his head in with a radio. Something to that effect. Either way, during inspections at Officer Candidates School, the Marine Corps version of boot camp for officers, he was the Sergeant Instructor who asked the hardest, the craziest questions. No softballs. No, “Who’s the Old Man of the Marine Corps?” or “What’s your first general order?” The first time he paced down the squad bay, all of us at attention in front of our racks, he grilled the would-be infantry guys with, “Would it bother you, ordering men into an assault where you know some will die?” and the would-be pilots with, “Do you think you could drop a bomb on an enemy target, knowing you might also kill women and kids?”

When he got to me, down at the end, he unloaded one of his more involved hypotheticals. “All right candidate. Say you think there’s an insurgent in a house and you call in air support, but then when you walk through the rubble there’s no insurgents, just this dead Iraqi civilian with his brains spilling out of his head, his legs still twitching and a little Iraqi kid at his side asking you why his father won’t get up. So. What are you going to tell that Iraqi kid?”

Amid all the playacting of OCS—screaming “Kill!” with every movement during training exercises, singing cadences about how tough we are, about how much we relish violence—this felt like a valuable corrective. In his own way, that Sergeant Instructor was trying to clue us in to something few people give enough thought to when they sign up: joining the Marine Corps isn’t just about exposing yourself to the trials and risks of combat—it’s also about exposing yourself to moral risk.

I never had to explain to an Iraqi child that I’d killed his father. As a public affairs officer, working with the media and running an office of Marine journalists, I was never even in combat. And my service in Iraq was during a time when things seemed to be getting better. But that period was just one small part of the disastrous war I chose to have a stake in. “We all volunteered,” a friend of mine and a five-tour Marine veteran, Elliot Ackerman, said to me once. “I chose it and I kept choosing it. There’s a sort of sadness associated with that.”

As a former Marine, I’ve watched the unraveling of Iraq with a sense of grief, rage, and guilt. As an American citizen, I’ve felt the same, though when I try to trace the precise lines of responsibility of a civilian versus a veteran, I get all tangled up. The military ethicist Martin Cook claims there is an “implicit moral contract between the nation and its soldiers,” which seems straightforward, but as the mission of the military has morphed and changed, it’s hard to see what that contract consists of. A decade after I joined the Marines, I’m left wondering what obligations I incurred as a result of that choice, and what obligations I share with the rest of my country toward our wars and to the men and women who fight them. What, precisely, was the bargain that I struck when I raised my hand and swore to defend my country against all enemies, foreign and domestic?

Grand causes

It was somewhat surprising (to me, anyway, and certainly to my parents) that I wound up in the Marines. I wasn’t from a military family. My father had served in the Peace Corps, my mother was working in international medical development. If you’d asked me what I wanted to do, post-college, I would have told you I wanted to become a career diplomat, like my maternal grandfather. I had no interest in going to war.

Operation Desert Storm was the first major world event to make an impression on me—though to my seven-year-old self the news coverage showing grainy videos of smart bombs unerringly finding their targets made those hits seem less a victory of soldiers than a triumph of technology. The murky, muddy conflicts in Mogadishu and the Balkans registered only vaguely. War, to my mind, meant World War II, or Vietnam. The first I thought of as an epic success, the second as a horrific failure, but both were conflicts capable of capturing the attention of our whole society. Not something struggling for air-time against a presidential sex scandal.

So I didn’t get my ideas about war from the news, from the wars actually being fought during my teenage years. I got my ideas from books.

My novels and my history books were sending very mixed signals. War was either pointless hell, or it was the shining example of American exceptionalism.

Reading novels like Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, or Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, I learned to see war as pointless suffering, absurdity, a spectacle of man’s inhumanity to man. Yet narrative nonfiction told me something different, particularly the narrative nonfiction about World War II, a genre really getting off the ground in the late-90s and early aughts. Perhaps this was a belated result of the Gulf War, during which the military seemed to have shaken off its post-Vietnam malaise and shown that, yes, goddamn it, we can win something, and win it good. Books like Stephen Ambrose’s Band of Brothers and Tom Brokaw’s The Greatest Generation went hand-in-hand with movies like Saving Private Ryan to present a vision of remarkable heroism in a world that desperately needed it.

11 230 128 34

11 March 1969

11 230 128 34

11 March 1969

In short, my novels and my histories were sending very mixed signals. War was either pointless hell, or it was the shining example of American exceptionalism. In middle-school, I’d read Ambrose’s Citizen Soldiers, about the European Theater in World War II. More than anything else, it was the title that stayed with me, the notion of service in a grand cause as the extension of citizenship. I never bothered to consider that the mix of draftees and volunteers who served in World War II wasn’t so different from the mix of draftees and volunteers who served in Vietnam, or that the atrocities committed in that war were no less horrific than those committed in Vietnam, though no one was likely to write a best-selling book about Vietnam entitled Citizen Soldiers. The title appealed to me. Deeply. But I didn’t see any grand causes in the 1990s, just a series of messy, limited engagements. Of course, in the history of American warfare, from the Indian Wars to the Philippines to the Banana Wars, it was the grand causes that were the anomalies, not the brushfire wars at the edge of empire.

Then 9/11 happened. We all have our stories of where we were that day. Mine is that I was in the woods, hiking the Appalachian Trail. As my little group of hikers scrambled over the rough paths we kept running into people telling stories of planes hitting the World Trade Center. It sounded preposterous, the sort of rumor that could easily spread in an isolated place, in the days before everybody had a smartphone. But we kept hearing the story, in ever more detail, until it became clear—particularly for those of us from New York—that we had to leave the woods.

I can’t say that I joined the military because of 9/11. Not exactly. By the time I got around to it the main U.S. military effort had shifted to Iraq, a war I’d supported though one which I never associated with al-Qaida or Osama bin Laden. But without 9/11, we might not have been at war there, and if we hadn’t been at war, I wouldn’t have joined.

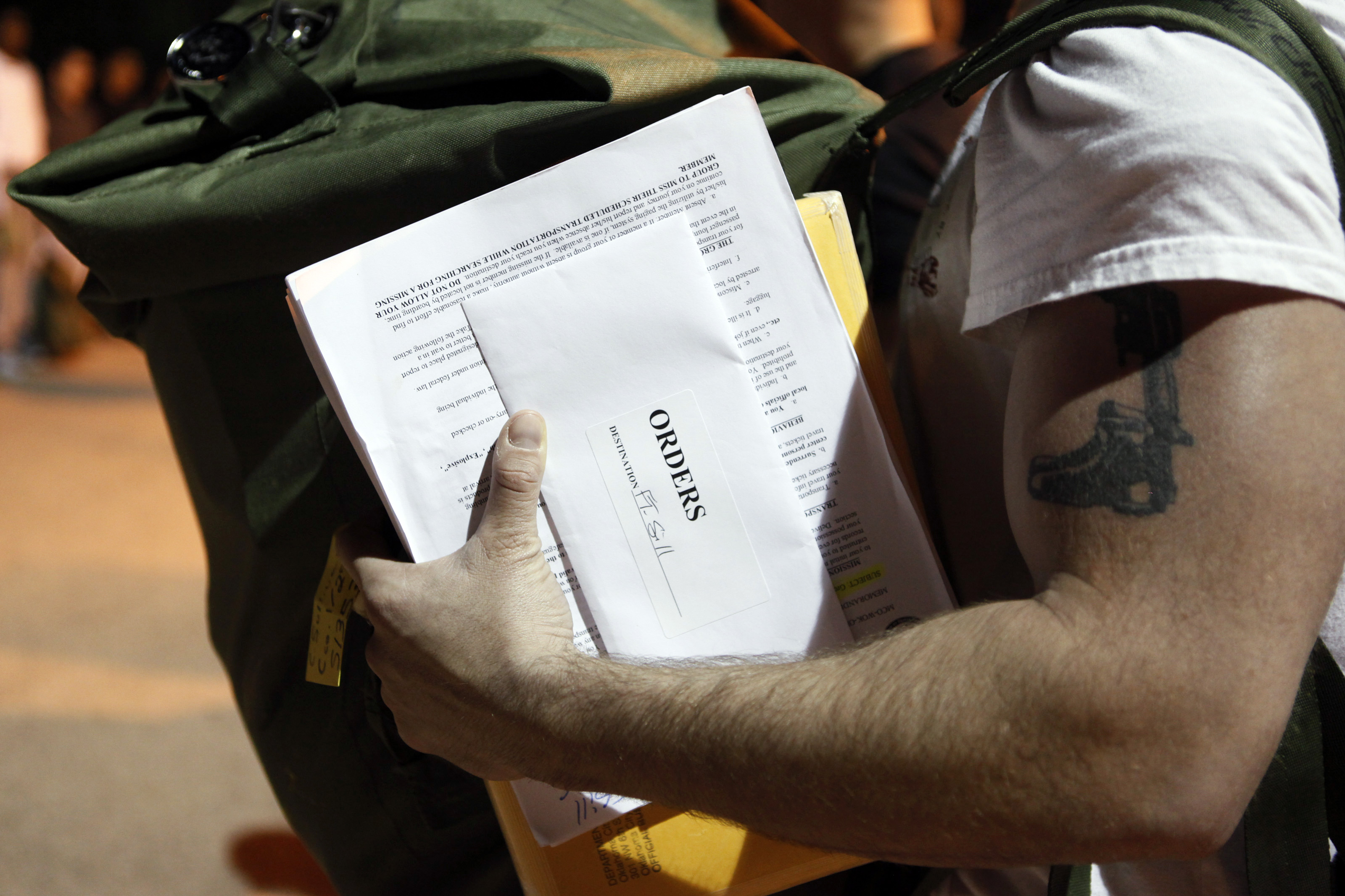

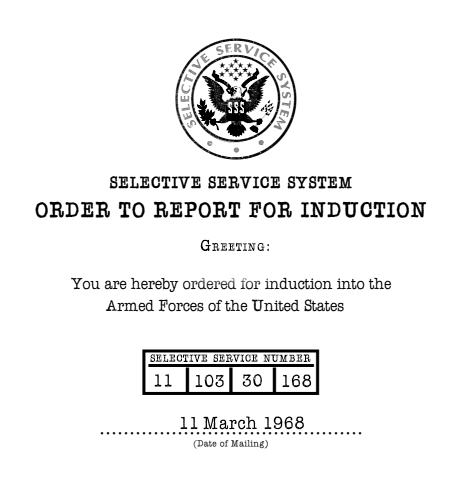

It was a strange time to make the decision, or at least, it seemed strange to many of my classmates and professors. I raised my hand and swore my oath of office on May 11, 2005. It was a year and a half after Saddam Hussein’s capture. The weapons of mass destruction had not been found. The insurgency was growing. It wasn’t just the wisdom of the invasion that was in doubt, but also the competence of the policymakers. Then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld had been proven wrong about almost every major post-invasion decision, from troop levels to post-war reconstruction funds. Anybody paying close attention could tell that Iraq was spiraling into chaos, and the once jubilant public mood about our involvement in the war, with over 70 percent of Americans in 2003 nodding along in approval, was souring. But the potential for failure, and the horrific cost in terms of human lives that failure would entail, only underscored for me why I should do my part. This was my grand cause, my test of citizenship.

Citizen-soldiers versus “base hirelings”

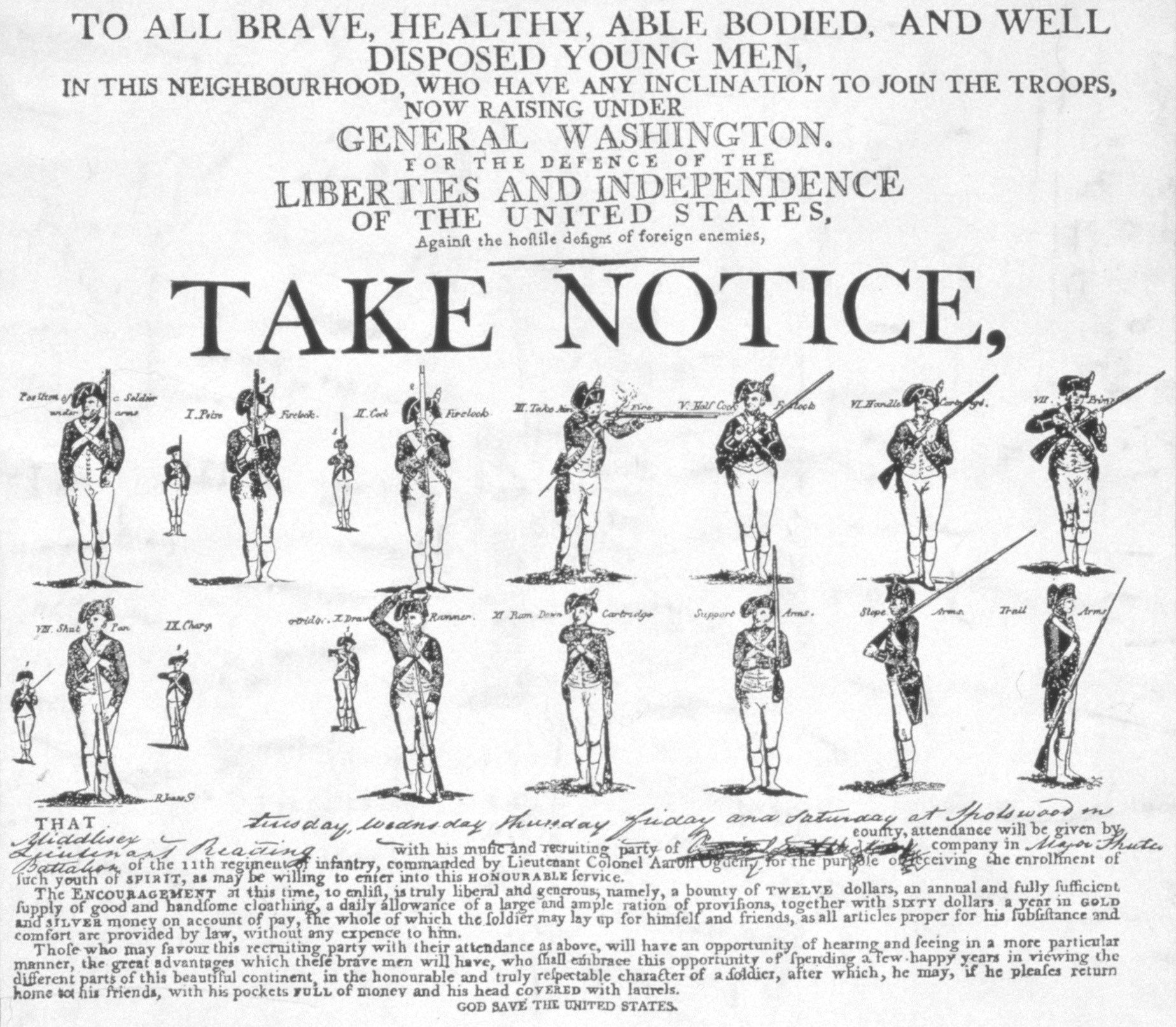

The highly professional all-volunteer force I joined, though, wouldn’t have fit with the Founding Fathers’ conception of citizen-soldiers. They distrusted standing armies: Alexander Hamilton thought Congress should vote every two years “upon the propriety of keeping a military force on foot”; James Madison claimed “armies kept up under the pretext of defending, have enslaved the people”; and Thomas Jefferson suggested the Greeks and Romans were wise “to put into the hands of their rulers no such engine of oppression as a standing army.”

They wanted to rely on “the people,” not on professionals. According to the historian Thomas Flexner, at the outset of the Revolutionary War George Washington had grounded his military thinking on the notion that “his virtuous citizen-soldiers would prove in combat superior, or at least equal, to the hireling invaders.” This was an understandably attractive belief for a group of rebellious colonists with little military experience. The historian David McCullough tells us that the average American Continental soldier viewed the British troops as “hardened, battle-scarred veterans, the sweepings of the London and Liverpool slums, debtors, drunks, common criminals and the like, who had been bullied and beaten into mindless obedience.”

Even lower in their eyes were the Hessian troops the British had hired to fight the colonists, which were commanded by Lieutenant-General Leopold Philip von Heister. A veteran of many campaigns, von Heister had crankily sailed over from England, touched shore, “called for hock and swallowed large potations to the health of his friends,” and then, apparently, set out trying to kill Americans.

There’s a long tradition of distrust for mercenaries, from Aristotle claiming they “turn cowards … when the danger puts too great a strain on them” to Machiavelli arguing they’re “useless and dangerous … disunited, ambitious and without discipline, unfaithful, valiant before friends, cowardly before enemies,” and the colonists would likely have agreed with such assessments. Mercenaries were at the bottom of the hierarchy of military excellence, citizen-soldiers at the top. We can see this view reflected in George Washington’s message to his soldiers before the first major engagement of the Revolutionary War, the Battle of Long Island:

Remember, officers and Soldiers, that you are Freemen … Remember how your Courage and Spirit have been despised, and traduced by your cruel invaders, though they have found by dear experience at Boston, Charlestown and other places, what a few brave men contending in their own land, and in best of causes can do, against base hirelings and mercenaries.

This was in August 1776, and Washington’s 19,000 men were about to see whether their civic virtues would triumph over British military skill. The American line stretched out across central Brooklyn, with British troops advancing from the south and the east. Though there was skirmishing during the day on August 26, the real fighting began the next morning when a column of Hessians marched up Battle Pass, in modern day Prospect Park.

What followed was a disaster. In the unkind phrasing of historian W.J. Wood, “Washington and his commanders … performed like ungifted amateurs,” and that’s exactly how the Hessian mercenaries viewed them. “The rebels had a very advantageous position in the wood,” wrote one Hessian soldier, “but when we attacked them courageously in their hiding-places, they ran, as all mobs do.” Colonel Heinrich von Heeringen, the commander of a Hessian regiment, wrote, “The riflemen were mostly spitted to the trees with bayonets. These frightful people deserve pity rather than fear.” And looking over those he’d captured, von Heeringen sneered, “among the prisoners are many so-called colonels, lieutenant-colonels, majors, and other officers, who, however, are nothing but mechanics, tailors, shoe-makers, wig-makers, barbers, etc. Some of them were soundly beaten by our people, who would by no means let such persons pass for officers.”

It was a rough education for Washington. At the close of the war he would submit to Congress his Sentiments on a Peace Establishment, which noted that “Altho’ a large standing Army in time of Peace hath ever been considered dangerous to the liberties of a Country, yet a few Troops, under certain circumstances, are not only safe, but indispensably necessary.” Congress, however, rejected the idea of even a modest standing army for the nation, its only concession being to keep one standing regiment and a battery of artillery. The rest of the new nation’s defense would rely mostly on state militias. Hence the Second Amendment. This idealistic vision of militias as a bulwark of democracy would soon face a harsh reality check.

There continues to be a cynicism about the motives of those who volunteer for the military. I’ve been repeatedly told that people don’t really enlist because they want to, but because they have to.

In this case, it was not the British, but the Western Confederacy of American Indians who’d give the Americans their comeuppance. Mixed units of American regulars and militiamen had been fighting these tribes throughout the early 1790s. The first campaign, led by General Josiah Harmar, was meant “to chastise the Indian Nations who have of late been so troublesome.” Today, the campaign is known as Harmar’s Defeat, which tells you all you really need to know about whether or not that happened. The individual battles within that campaign don’t have much better titles. There’s Hardin’s Defeat, Hartshorn’s Defeat, the Battle of Pumpkin Fields. This last doesn’t sound so bad, until you learn that it supposedly got its name not because it was fought in a pumpkin field, but because the steam from the scalped skulls of militiamen reminded the victorious American Indians of squash steaming in the autumn air.

Harmar was succeeded by General Arthur St. Clair, who, though rather old, rather fat, and afflicted with gout, set out with “sanguine expectations that a severe blow might be given to the savages yet.” His poorly trained, undisciplined men engaged an equal-sized force at the Battle of the Wabash in November 1791, also known by the considerably more evocative title, the Battle of a Thousand Slain. What followed was the worst military disaster of U.S. history. Of St. Clair’s 920 troops, 632 were killed and 264 wounded, a casualty rate of just over 97 percent. Congress, finally conceding that professionalism did count for something, bowed to the creation of a standing army beyond absolute bare bones.

Of course, the creation of the Army hardly ended the complicated relationship Americans had with professional soldiers. When we come to the Civil War, the first war in which we instituted a national draft, none other than Ulysses S. Grant would call the professional soldiers who’d manned the Army prior to the war “men who could not do as well in any other occupation.” Naturally, he was not talking about his own men, fine citizen-soldiers who “risked life for a principle … often men of social standing, competence, or wealth and independence of character.” It took a grand cause, then, like the Civil War, for military service to count as a civic virtue.

And not only was it a civic virtue—it could be what made you American in the first place. During World War I, Assistant Secretary of War Henry Breckinridge maintained that when immigrants and those born in this country rub “elbows in a common service to a common Fatherland … out comes the hyphen—up goes the Stars and Stripes … Universal military service will be the elder brother of the public school in fusing this American race.” During World War II, Franklin Delano Roosevelt thought military service would “Americanize” foreigners.

To this day, however, there continues to be a cynicism about the motives of those who volunteer for the military. I’ve been repeatedly told that people don’t really enlist because they want to, but because they have to. I remember seeing the poet and playwright Maurice Decaul, frustrated with an insistent questioner who couldn’t accept that an intelligent and sensitive soul might want to join the military, finally just blurt out, “I wanted to join the Marine Corps since I was eight years old.” And all the veterans I know who are Ivy League graduates have had the unpleasant experience of people acting as though they’d made some sort of bizarre choice to spend time with the peons. At one event a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist explained to me that, though he felt the Iraq War was evil, he didn’t feel the soldiers should be blamed for their participation—they were only in service because they had no other options.

This is the “poverty draft”—the idea that with the elimination of the draft, we shifted the burden from the whole of society to only the most poor and disadvantaged, who join the military to get a step up in life and then become cannon fodder. The demographics of the military don’t support the image—it’s actually the middle class that’s best represented in the military, and the numbers of high-income and highly educated recruits rose to levels disproportionate to their percentage of the population after the war on terror began. But this notion of a military filled with ne’er-do-wells who are in it only for the money is frustrating not just because it’s insulting or false—it takes the decision to put one’s life at risk for one’s country and transforms it, as if by magic, into a self-interested act. Veterans have a benefit package … they’re paid in full, right? If the war was a just one and they saved the world against fascism, or slavery, maybe more is owed. If not, well, you can pity them, but you can’t take them seriously as moral agents.

Messing up your nice, clean soul

The decision to accept my commission was the most important one I’d made in my twenty-one years of life, and I knew it. I also knew I’d likely end up in Iraq, that the next four years would be bound up with a politically and morally contentious conflict, and I was comfortable with that. But in 2005, it didn’t seem to me that my decision about whether or not to join would make me any the more or less responsible for a war that had started in 2003. There’s a bit in John Osbourne’s play Look Back in Anger where a character angrily tells his wife:

It’s no good trying to fool yourself about love. You can’t fall into it like a soft job without dirtying up your hands. It takes muscle and guts. If you can’t bear the thought of messing up your nice, clean soul you better give up the whole idea of life, and become a saint. Because you’ll never make it as a human being.

As in love, so in politics. Choices have to be made, without the benefit of hindsight, and then you have to live with those choices. The chain of events begun with the invasion of Iraq would neither end nor alter through my own inaction. So when friends would argue with me about WMDs or the initial invasion it seemed radically beside the point. I didn’t have a time machine, neither did they. Nor could I write off the entire war effort as evil and thereby evade any feeling of responsibility for all the policy decisions that came later.

Back in 2006, as I was preparing to go to Anbar Province, the “lost” province, the heart of the Sunni insurgency, it was tempting to think there was nothing we could do to improve the situation in Iraq, or even that doing nothing was somehow the best course of action. The following year Senator Carl Levin would propose a rapid withdrawal in order to somehow magically force an Iraqi political settlement. “It is time for Congress to explain to the Iraqis that it is your country,” he said in a speech before Congress, apparently under the impression that the Iraqis didn’t know that. To me, this proposal for ending the occupation seemed little more than a smokescreen to allow us to leave Iraq behind without feeling too guilty about it.

Though the word “occupation” is often bandied about as though it represents something inherently evil, occupation is actually a situation legitimized—and circumscribed—by international law. Article 43 of the Hague Regulations of 1907 demands that an occupying force “shall take all the measures in [its] power to restore and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety.” Further obligations are spelled out in the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949. These apply regardless of whether the war waged against the occupied country was just or unjust. We waged a just war against Germany and Japan during World War II and yet afterward still had an obligation to provide order for those countries’ citizens, many of whom were starving, homeless refugees. For me, it didn’t follow that because a war was unjust we were thereby relieved of our obligations as a country and could happily leave Iraqis to their sorry fate, secure in the knowledge that our hands were clean as long as we hadn’t voted for George W. Bush in 2000. We obviously hadn’t lived up to our obligations to prevent chaos in the aftermath of our invasion of Iraq.

Of course, none of that means that the deployment I was about to go on would, in fact, be part of an adequate or just national response to the tragedy unfolding there.

We can tell them the truth when we get home

In the first month of my deployment, a suicide truck bomber detonated among a group of families going to mosque. U.S. forces brought the injured in to our base hospital, where the line of Marines waiting to give blood was so long that it extended out the door and wrapped around the building. Inside there were so many injured that the doctors ran out of trauma tables and had to do surgery on the floor. In one room, I saw them slowly stitching a man’s intestines back together. In another, a surgeon new to the theater hesitated before a man’s bloody, shrapnel-filled body. Time being of the essence, a doctor who’d been there several months already pushed him away, stuck a finger into the man’s side, plunged it knuckle deep, and pulled out a jagged piece of metal from his abdomen.

Not much later a similar attack hit Ramadi. One of my Marines, a videographer, asked if he could interview one of our doctors after the attack. The only quiet place was where they were keeping the bodies of the dead, so the two sat in a corner, surrounded by civilian bodies, the men, women, and children the doctors hadn’t been able to save. There, in the silence, the exhausted doctor wept.

The units moving out of theater around this time—doctors, infantryman, engineers, and logisticians—had seen a lot of violence, but not much progress. I remember listening in on an outgoing group of soldiers talking about what they should tell their families back home about the war. They couldn’t tell them the truth, they agreed. Instead, they’d tell them proud, uplifting things. “We can tell them the truth when we get home,” one said. It was quiet a moment, and another asked, “Will we even tell the truth then.”

That was early 2007. By 2008, violence had fallen, markets were opening up, and police forces were swelling. The slowdown in death threw opponents of the U.S. troop surge for a loop. Moveon.org famously suggested General David Petraeus was “cooking the books.” More thoughtful critics came up with other responses: the gains were temporary, dependent on a political solution, or on untrustworthy allies, or on arming one side in a civil war. Or, less plausibly, given the actual patterns of violence in Iraq, maybe sectarian cleansing had sorted the country into Sunni and Shia enclaves and so the violence had declined only because there was no one left to kill. Even today, whether the surge “worked” is the subject of a fairly intense debate both within the military and outside of it. It’s clear the Anbar Awakening—the Sunni revolt against Al Qaeda in Iraq—could not have reshaped the country in the way it did without significant U.S. support. But those who argue that the surge didn’t solve Iraq’s underlying issues are, of course, completely correct, and whether the Bush administration was right to pursue the surge in 2007 remains up for debate. Either way, it wasn’t enough.

I didn’t know that in 2008. I went home feeling great about my deployment. Iraq was getting better, and I’d been part of the force (even if a rear-echelon part) that had risked life and limb for that goal. And the good news kept coming. A year and a half after I got back, the New York Times had a story about a giant beach party thrown on the banks of Lake Habbaniyah, near where I’d spent much of my time overseas. Photos showed hundreds of young Iraqis having fun. A DJ yelled into a microphone: “Shoutout to everyone from Baghdad. Everyone from Adhamiyah and Sadr City.” I spoke with another Marine who’d spent time in that area—the author Michael Pitre. He told me, “I remember reading that article and thinking, My God, did we win.”

I hoped so. Either way, I didn’t feel I had anything to account for. I was under the impression that history had justified me. And though I’m a Catholic, it never even occurred to me to do something once common for soldiers after war—seek atonement.

Coming back from Iraq, with none of the memories of visceral horror we associate with the authentic experience of war, I assumed my hands were clean.

In the medieval period, Christian theology carved out a space for war—what we now call “just war theory.” Nevertheless, killing was still considered a sin, even in a just war, even when lawful, even when the Church itself had directed you to do it. One of the more remarkable consequences of this belief is the Penitential Ordinance imposed on Norman knights who fought with William the Conqueror on Senlac Hill at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. “Anyone who knows that he killed a man in the great battle must do penance for one year for each man that he killed,” it proclaims, before moving forward and really getting into the weeds. If you wounded a man and aren’t sure he died, forty days penance. If you fought only for gain, it’s the same penance as if you’d committed a regular homicide. For archers, “who killed some and wounded others, but are necessarily ignorant as to how many,” three Lents worth of penance.

To modern, rational ears, there seems something bizarre, if not cruel about demanding something of men and then demanding penance for that same thing. And yet it is perhaps healthier both for the society that sends men to war and for the warriors themselves. Vietnam veteran Karl Marlantes, looking back on his time overseas, described himself “struggling with a situation approaching the sacred in its terror and contact with the infinite.” Though he didn’t know it then, what he desperately wanted was a spiritual guide. “We cannot expect normal eighteen-year-olds to kill someone and contain it in a healthy way. They must be helped to sort out what will be healthy grief about taking a life because it is part of the sorrow of war.”

This route might offer not only redemption, but also genuine growth as a human being. The philosopher and World War II veteran J. Glenn Gray wrote that for a soldier, “guilt can teach him, as few things else are able to, how utterly a man can be alienated from the very sources of his being. But the recognition may point the way to a reunion and a reconciliation with the varied forms of the created. … Atonement will become for him not an act of faith or a deed, but a life, a life devoted to strengthening the bonds between men and between man and nature.”

But this is a way of thinking distinctly at odds with stories of uncomplicated military glory. “The notion of war as sin simply doesn’t play in Peoria—or anywhere else in the United States—because a fondness for war is an essential component of the macho American God,” wrote Vietnam War chaplain William Mahedy. “Yet the awareness of evil—in religious terms of consciousness of sin—is the underlying motif of the Vietnam War stories.” And of course, it’s not just Vietnam. This is a recurrent theme in writing from both the wars we celebrate and the wars we condemn. During an interview, I once cautiously asked a ninety-one-year-old veteran of World War II what he thought of the idea of the Greatest Generation. “It’s bullshit!” he shouted, cutting me off. “Bullshit … War ruined my life.” He later calmed and revised his self-assessment: “I’m eighty percent sweet and twenty percent bitter.” And the twenty percent of bitterness he still held with him, over seven decades later, came from his experiences in what we like to think of as “the Good War.”

In terms of the contract young Marines and soldiers sign when joining the service, this moral dimension can be added to the physical and emotional risks they assume, risks present regardless of how we later come to feel about the particular war we send them off to. “Men wash their hands, in blood, as best they can,” wrote the poet Randall Jarrell. Coming back from Iraq, with none of the memories of visceral horror we associate with the authentic experience of war, I assumed my hands were clean. As a staff officer, I had the privilege of seeing the war mostly as a spectator, the same privilege enjoyed by the rest of the American public—that is, if they bothered to look.

A saving idea?

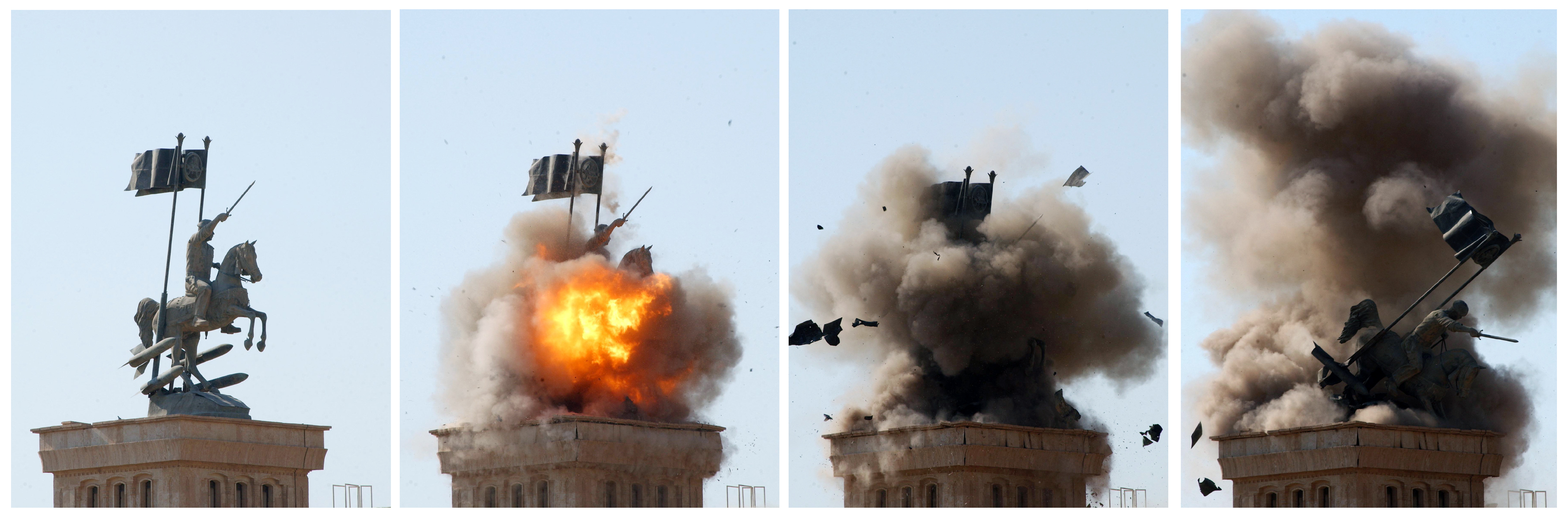

Not long after ISIS had made headlines by seizing Fallujah and Ramadi I went to the screening of a documentary about Afghanistan. During the Q&A with the director afterward one of the many veterans there stood up. He was a big, tough-looking guy, must have been the perfect image of a Marine in dress blues. He said, “I’m a veteran of Iraq. That used to be something I was incredibly proud of. If you’d asked me, just a few years ago, to make a resume of my life—not a resume for a job, but a resume of who I was, what I was—all the biggest bullet points would have been: Marine sergeant; combat veteran; led Marines in Iraq. But now, I’m looking at what’s happening in Iraq, and I’m starting to wonder what I was a part of, and whether I can be proud of it. Was I part of an evil thing? Because if I was, then I don’t know who I am anymore. I don’t know what my identity is.”

It was a sharper-edged response to the overseas tragedy than I’d previously heard. Though I’d seen many veterans wondering “What was this all for?” they often resolved the question by narrowing their focus. One veteran who served in the Second Battle of Fallujah argued that he didn’t think about “Bush or Obama, or about Iraq or Afghanistan,” but about the men he’d served with and “what we’d done for each other.” Elizabeth Samet, an instructor at West Point, argues that our recent wars’ “absence of a clear and consistent political vision … forced many of the platoon leaders and company commanders I know to understand the dramas in which they found themselves as local and individual rather than national or communal. The ends they furnish for themselves—coming home without losing any soldiers or, if someone has to die, doing so heroically in battle—offer exclusively personal and particular consolations that make the mission itself effectively beside the point.”

In its own way, American pop culture, with its increasing obsession with Special Forces conducting commando-style raids, seems to have come to a similar conclusion. Zero Dark Thirty, 13 Hours, and American Sniper offer a vision of war in which highly trained operatives kill undoubtedly evil people—bomb-makers and torturers and sadists and thugs of all stripes—without forcing too much consideration about the overall outcome. In a raid, the moral stakes seem clear. Let’s think only about killing “the Butcher,” or the evil enemy sniper, or Osama bin Laden, not about ending the chaos swirling around them. And though these movies have the veneer of non-fiction, their impact isn’t so different from the previous generation’s Rambo franchise, which Vietnam veteran and author Gustav Hasford argued “satisfies our pathetic need to win the war and gives us another coat of whitewash as bumbling do-gooders, innocent American white-bread boy[s], pulled down into corruption by wicked Orientals. We should have won, and we could have won, Rambo argues, if only the dumb grunts could have been saved by grotesquely muscled civilians who somehow skated the shooting war.”

This kind of thinking has become operative not just in the movies but in real life. At his State of the Union Address, President Obama proclaimed earlier this year, “if you doubt America’s commitment—or mine—to see that justice is done, just ask Osama bin Laden. Ask the leader of Al Qaeda in Yemen, who was taken out last year, or the perpetrator of the Benghazi attacks.” He received applause, and it’s not hard to understand why. Since these kinds of missions don’t put troops in the position of holding territory, when we kill or capture a target we can mark that off as a success regardless of whether or not we’re making a positive impact on the region we’re striking. Never mind what’s actually happening on the ground in Libya and Yemen right now. If you narrow your scope sufficiently, there’s no end to what you don’t have to deal with.

It’s true that, in the middle of a deployment, the specifics of any individual unit’s experience and the bonds those Marines share might overshadow their sense of the broader mission. But people join the military to be a part of something greater than themselves, and ultimately it’s deeply important for service members to be able to feel their sacrifices had a purpose.

Joining the military is an act of faith in one’s country—an act of faith that the country will use your life well.

Pat C. Hoy II, a New York University professor who served in Vietnam, once described the aftermath of a battle in Vietnam waged by soldiers he’d trained. It had gratified him to see those soldiers recover “through the saving rituals they performed together—burying the dead, policing the battlefield, stacking ammunition, burning left-over powder bags, hauling trash, shaving, drinking coffee, washing, talking as they restored order and looked out for one another’s welfare.” These are the kind of small moments of communal satisfaction that I saw veteran after veteran invoke as they tried to come to terms with the extent of our failure in Iraq. For Hoy, such satisfactions are real, but insufficient.

Those men had done the soldiers’ dirty job in a war that will probably never end—for them or for this nation. The Vietnam War will not be transfigured by a purifying idea. The men and women who fought there will forever be haunted by the fact of carnage itself. The ones who actually looked straight into the eyes of death will scream out in the middle of the night and awake shaking in cold sweat for the rest of their lives—and there will be no idea, nothing save the memory of teamwork, to redeem them. That will not be enough. That loneliness is what they get in return for their gift of service to a nation that sent them out to die and abandoned them to their own saving ideas when they came home.

What is the saving idea of Iraq? In some ways, joining the military is an act of faith in one’s country—an act of faith that the country will use your life well. What your piece of a war will be, after all, is mostly a matter of chance. I have friends who joined prior to 9/11, when machine gun instructors still taught recruits to depress the trigger as long as it takes to say, “Die, commie, die!” I have friends who joined after 9/11, expecting to fight al-Qaida, only to invade Iraq. One friend protested the Iraq War, then signed up because he felt the war was unjust and so we owed the Iraqis a humane, responsible occupation. The Army sent him to Afghanistan twice. Another soldier I know, a reservist, had a unit slotted for one of two deployments—either to help with the Ebola crisis, a mission few would object to, or to man Guantanamo Bay. Depending on where they were sent, they knew they’d face radically different reactions when they came home. Of course, the praise or censure your average American civilian might dole out to those soldiers would in reality just be the doling out of the praise or censure they themselves deserve for being part of a nation that does such things.

The difference, though, is that it’s impossible for the veteran to pretend he has clean hands. No number of film dramatizations of commandos killing bad guys can move us past the simple reality that Iraq is destroyed, there is untold suffering overseas, and we as a country have even abandoned most of the translators who risked their lives for us.

Yet this fact seems not to have penetrated either the civilians we come home to, or the government that sent us: “How many American presidents or members of Congress have suffered from PTSD or taken their own lives rather than live any longer with the burden of having declared a war?” asked humanities professor Robert Emmet Meagher. None, of course.

Total mobilization

When my cell phone buzzed in a Brooklyn bar and the voice at the other end told me a Marine I’d served with had been shot in Afghanistan, I looked around, searching for someone to talk to. The band setting up, the tattooed bartenders, any of them could have plausibly been a sympathetic ear. I’ve generally found civilians quite interested once you take the effort. And yet … I couldn’t. It would, I suspected, be treated as a personal tragedy, as though I were delivering the news that a family member had been diagnosed with cancer. Not as something that implicated them.

There’s a joke among veterans, “Well, we were winning Iraq when I was there,” and the reason it’s a joke is because to be in the military is to be acutely conscious of how much each person relies on the larger organization. In boot camp, to be called “an individual” is a slur. A Marine on his or her own is not a militarily significant unit. At the Basic School, the orders we were taught to write always included a lost Marine plan, which means every order given carries with it the implicit message: you are nothing without the group. The Bowe Bergdahl case is a prime example of what happens when one soldier takes it upon himself to find the war he felt he was owed—a chance to be like the movie character Jason Bourne, as Bergdahl explained on tapes played by the podcast Serial. The intense anger directed at Bergdahl from rank and file soldiers, an anger sometimes hard for a civilian public raised on notions of American individualism to comprehend, is the anger of a collective whose members depend on each other for their very lives directed toward one who, through sheer self-righteous idiocy, violated the intimate bonds of camaraderie. By abandoning his post in Afghanistan, Bergdahl made his fellow soldiers’ brutally hard, dangerous, and possibly futile mission even harder and more dangerous and more futile, thereby breaking the cardinal rule of military life: don’t be a buddy fucker. You are not the hero of this movie.

But a soldier doesn’t just rely on his squad-mates, or on the leadership of his platoon and company. There’s close air support, communications, and logistics. Reliable weapons, ammunition, and supplies. The entire apparatus of war—all of it ultimately resting on American industry and on the tax dollars that each of us pays. “The image of war as armed combat merges into the more extended image of a gigantic labor process,” wrote Ernst Jünger, a German writer and veteran of World War I. After the Second World War Kurt Vonnegut would come to a similar conclusion, reflecting not only on the planes and crews, the bullets and bombs and shell fragments, but also where those came from: the factories “operating night and day,” the transportation lines for the raw materials, and the miners working to extract them. Think too hard about the front-line soldier, you end up thinking about all that was needed to put him there.

Today, we’re still mobilized for war, though in a manner perfectly designed to ensure we don’t think about it too much. Since we have an all-volunteer force, participation in war is a matter of choice, not a requirement of citizenship, and those in the military represent only a tiny fraction of the country—what historian Andrew Bacevich calls “the 1 percent army. “ So the average civilian’s chance of knowing any member of the service is correspondingly small.

Moreover, we’re expanding those aspects of warfighting that fly under the radar. Our drone program continues to grow, as does the special operations forces community, which has expanded from 45,600 special forces personnel in 2001 to 70,000 today, with further increases planned. The average American is even less likely to know a drone pilot or a member of a special ops unit—or to know much about what they actually do, either, since you can’t embed a reporter with a drone or with SEAL Team 6. Our Special Operations Command has become, in the words of former Lieutenant Colonel John Nagl, “an almost industrial-scale counterterrorism killing machine.”

Since we have an all-volunteer force, participation in war is a matter of choice, not a requirement of citizenship, and those in the military represent only a tiny fraction of the country.

Though it’s true that citizens do vote for the leaders who run this machine, we’ve absolved ourselves from demanding a serious debate about it in Congress. We’re still operating under a decade-old Authorization for Use of Military Force issued in the wake of 9/11, before some of the groups we’re currently fighting even existed, and it’s unlikely, despite attempts from Senators Tim Kaine (D-Va.) and Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.), that Congress will issue a new one any time soon. We wage war “with or without congressional action,” in the words of President Obama at his final State of the Union Address, which means that the American public remains insulated from considering the consequences. Even if they voted for the president ordering these strikes, there’s seemingly little reason for citizens to feel personally culpable when they go wrong.

It’s that sense of a personal stake in war that the veteran experiences viscerally, and which is so hard for the civilian to feel. The philosopher Nancy Sherman has explained post-war resentment as resulting from a broken contract between society and the veterans who serve. “They may feel guilt toward themselves and resentment at commanders for betrayals,” she writes, “but also, more than we are willing to acknowledge, they feel resentment toward us for our indifference toward their wars and afterwars, and for not even having to bear the burden of a war tax for over a decade of war. Reactive emotions, like resentment or trust, presume some kind of community—or at least are invocations to reinvoke one or convoke one anew.”

The debt owed them, then, is not simply one of material benefits. There’s a remarkable piece in Harper’s Magazine titled, “It’s Not That I’m Lazy,” published in 1946 and signed by an anonymous veteran, which argues, “There’s a kind of emptiness inside me that tells me that I’ve still got something coming. It’s not a pension that I’m looking for. What I paid out wasn’t money; it was part of myself. I want to be paid back in kind, in something human.”

That sounds right to me: “something human,” though I’m not sure what form it would take. When I first came back from Iraq, I thought it meant a public reckoning with the war, with its costs not just for Americans but for Iraqis as well. As time goes by, and particularly as I watch a U.S. presidential debate in which candidates have offered up carpet bombing, torture, and other kinds of war crimes as the answer to complex problems that the military has long since learned will only worsen if we attempt such simplistic and immoral solutions, I’ve given up on hoping that will happen anytime soon. If the persistence of U.S. military bases named after Confederate generals is any indication, it might not happen in my lifetime. The Holocaust survivor Jean Améry, considering Germany’s post-war rehabilitation, would conclude, “Society … thinks only about its continued existence.” Decades later Ta-Nehisi Coates, considering the difficulty, if not impossibility, of finding solutions for various historic tragedies, would write, “I think we all see our ‘theories and visions’ come to dust in the ‘starving, bleeding, captive land’ which is everywhere, which is politics.”

Bringing the mission home

Despite this, I don’t see nihilism from my fellow veterans. I see the opposite. I’ve met veterans who, horrified by the human cost of our wars overseas, have joined groups like the International Refugee Assistance Project or the International Rescue Committee. I’ve met veterans who’ve gone into public service—one of whom also remained in a reserve unit because, as he put it to me, “I want to know the decisions I make might affect me personally.” I’ve met veterans who’ve lobbied Congress, worked to fight military sexual assault, established literary non-profits, or worked to make public service—military or otherwise—an expectation within American society. A recent analysis of Census data shows that, compared with their peers, veterans volunteer more, give more to charity, vote more often, and are more likely to attend community meetings and join civic groups. This is the kind of civic engagement necessary for the functioning of a democracy.

In 2007, Rhodes-scholar and Navy SEAL Eric Greitens made a visit to the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. The men and women he found there, including amputees and serious burn victims, generally were eager to return to their units, though that would in many cases be impossible. These vets had been repeatedly thanked for their service. They’d been assured they were heroes and that they had the support of a grateful nation. But, as recounted in Joe Klein’s book Charlie Mike, Greitens found what energized them was something different. Four words: “We still need you.”

Greitens, who is hoping to win the Republican nomination in the Missouri governor’s race this year, went on to found The Mission Continues, an organization that awards community-service fellowships that “redeploy” post-9/11 veterans back to their communities to work on projects from education to housing and beyond. One study found that, though these veterans had high rates of Traumatic Brain Injury (52 percent), PTSD (64 percent) and depression (28 percent), the opportunity to feel that they had made a contribution lead to remarkably positive post-fellowship experiences. Eighty-six percent reported that the fellowship was a positive, life-changing experience. Seventy-one percent went on to pursue further education, 86 percent transferred their military skills to civilian employment, and large majorities reported that the fellowships helped them become community leaders able to teach others the value of service.

“While most watch the suffering of the world on their TV, we ACT, rapidly and with great purpose,” wrote Marine sniper Clay Hunt, a veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan who provided relief efforts with the veteran-led disaster response organization Team Rubicon in the wake of earthquakes in Chile and Haiti, raised money for wounded veterans, and helped lobby Congress for veterans’ benefits. “Not counting the cost and without hope for reward. We simply refuse to watch our world suffer, when we have the skills and the means to alleviate some of that suffering, for as many people as we can reach … Inaction is not an option.”

Strengthening the bonds between men and between man and nature

Clay Hunt took his own life in March 2011. His story may be a heroic tale of a Marine who served with distinction and came home determined to continue serving, but it is also the much darker story of a Marine who was never able to get the help he himself needed. Once out of the Corps, Hunt struggled with the Veterans Administration over his disability rating and his treatment. He appealed the low level of his benefits only to face one bureaucratic hurdle after another, including the VA losing his files, the process dragging out for eighteen months. As for his medical care, he got almost no counseling for his post-traumatic stress, but was instead prescribed a variety of drugs, none of which seemed to help. He felt he’d been used as a “guinea pig” for one failed treatment after another. After moving to Houston he waited months for his first appointment with a psychiatrist, and then found the appointment so stressful he resolved never to return. Two weeks later he killed himself.

True integration back into society can be overwhelmingly difficult for veterans struggling with unbearable physical or mental injuries. Hence the bare minimum of the payment veterans are due: a reliable Veterans Administration, improved mental health care, and adequate help transitioning to the civilian sector. The Clay Hunt Suicide Prevention for American Veterans (SAV) Act that President Obama signed into law in 2015 is intended to address some of these needs.

But this is just a starting place. It does not fully repay the debt to a Marine suffering post-traumatic stress if we provide him access to competent mental health care, just as we don’t fully repay the debt to a soldier who lost a limb by handing her a well-made prosthetic. And in the wake of a war that has left whole societies shattered, hundreds of thousands of lives lost and more displaced, the debt cannot be solely to an individual, or even to a class of individuals, like veterans. A therapeutic approach, however necessary, can only heal wounds. Our problems run deeper than that.

No civilian can assume the moral burdens felt at a gut level by participants in war, but all can show an equal commitment to their country.

I began this essay contemplating the oath I swore as a Marine to support and defend the Constitution. At the time I took the oath it felt like a special and precious burden I was taking on—sworn to defend not simply the physical security of my homeland but to defend something broader, our founding document, and thus the set of ideals embedded within it. Years later, looking through the section in the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ “Citizen’s Almanac” on citizens’ responsibilities, I was embarrassed to realize my obligations as a Marine were not so unique. The very first responsibility listed is to “support and defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic.” So I had already owed that to my country, by virtue of my birth and the privilege of being American.

The divide between the civilian and the service member, then, need not feel so wide. Perhaps the way forward is merely through living up to those ideals, through action, and a greater commitment by the citizenry to the institutions of American civic life that so many veterans are working to rebuild. Teddy Roosevelt once claimed a healthy society would regard the man “who shirks his duty to the State in time of peace as being only one degree worse than the man who thus shirks it in time of war. A great many of our men … rather plume themselves upon being good citizens if they even vote; yet voting is the very least of their duties.” That seems right to me. The exact nature of those additional duties will depend on the individual’s principles. What is undeniable, though, is that there is always a way to serve, to help bend the power and potential of the United States toward the good.

No civilian can assume the moral burdens felt at a gut level by participants in war, but all can show an equal commitment to their country, an equal assumption of the obligations inherent in citizenship, and an equal bias for action. Ideals are one thing—the messy business of putting them into practice is another. That means giving up on any claim to moral purity. That means getting your hands dirty.